Doctors Remove Pig Kidney After Alabama Woman Lives with Transplant for Record 130 Days

Alabama Woman Has Pig Kidney Removed After Record-Breaking 130 Days

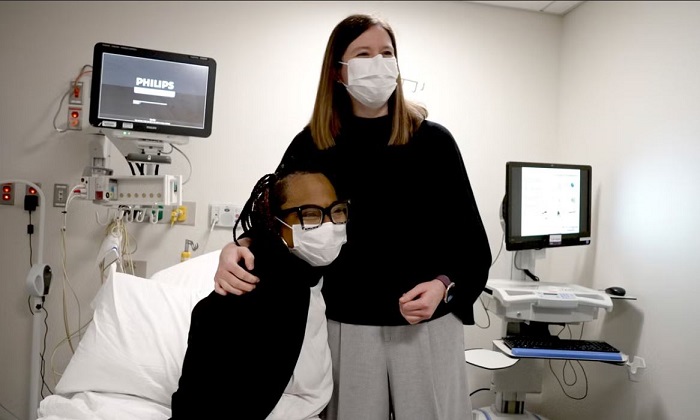

- Towana Looney, has returned home after surgeons removed a genetically-modified pig kidney

- The United States faces a critical shortage of donor organs

- Dr. Montgomery noted that the cause of the rejection is still under investigation.

An Alabama woman, Towana Looney, has returned home after surgeons removed a genetically-modified pig kidney that she had lived with for a record 130 days. The procedure took place a week ago, and Ms. Looney is now back on dialysis, a treatment necessary for individuals with kidney failure.

Xenotransplantation, the process of transplanting organs or tissues from non-human animals to humans, is an experimental field that holds the potential to significantly increase the supply of organs for those in need, according to researchers. The United States faces a critical shortage of donor organs, leading to an average of 13 deaths daily for those awaiting transplants. Additionally, inefficiencies in the system result in over 28,000 donated human organs going unused each year.

Despite the outcome not being what was hoped for, Ms. Looney expressed optimism in a statement, saying, “Though the outcome is not what anyone wanted, I know a lot was learned from my 130 days with a pig kidney – and that this can help and inspire many others in their journey to overcoming kidney disease.” She also thanked her medical team at NYU Langone Health in New York City for “the opportunity to be part of this incredible research.”

Prior to Ms. Looney’s transplant, only four other Americans had received genetically altered pig organs, including hearts and kidneys. However, none of these transplants lasted longer than two months, and the recipients, who were severely ill before surgery, did not survive. Notably, a man in New Hampshire who received a pig kidney in January is currently doing well.

Dr. Robert Montgomery, Ms. Looney’s surgeon, explained the decision to remove the kidney: “We did the safe thing. She’s no worse off than she was before (the xenotransplant) and she would tell you she’s better off because she had this 4.5-month break from dialysis.”

In xenotransplantation, the risks of infection and organ rejection from an animal organ are potentially higher than with human organs. It is also not yet fully understood if transplanted animal kidneys can perform all the functions of human kidneys, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

Dr. Montgomery noted that the cause of the rejection is still under investigation. Ms. Looney and her medical team agreed that removing the pig kidney was the most prudent course of action. He mentioned that Ms. Looney had a prior infection related to her dialysis and her immune-suppressing anti-rejection drugs were slightly reduced. Her immune system was also reactivating post-transplant, and the combination of these factors may have damaged the new kidney, he theorized. Ms. Looney had been on dialysis since 2016, and her body may have been unusually predisposed to reject a kidney. She received the pig kidney transplant last November.

Dr. Montgomery believes that Ms. Looney’s experience provides valuable insights for upcoming clinical trials in xenotransplantation. He emphasized that progress in making xenotransplants successful “is going to be won with singles and doubles, not swinging for the fence every time we do one of these.”